False Horns on Real Unicorns

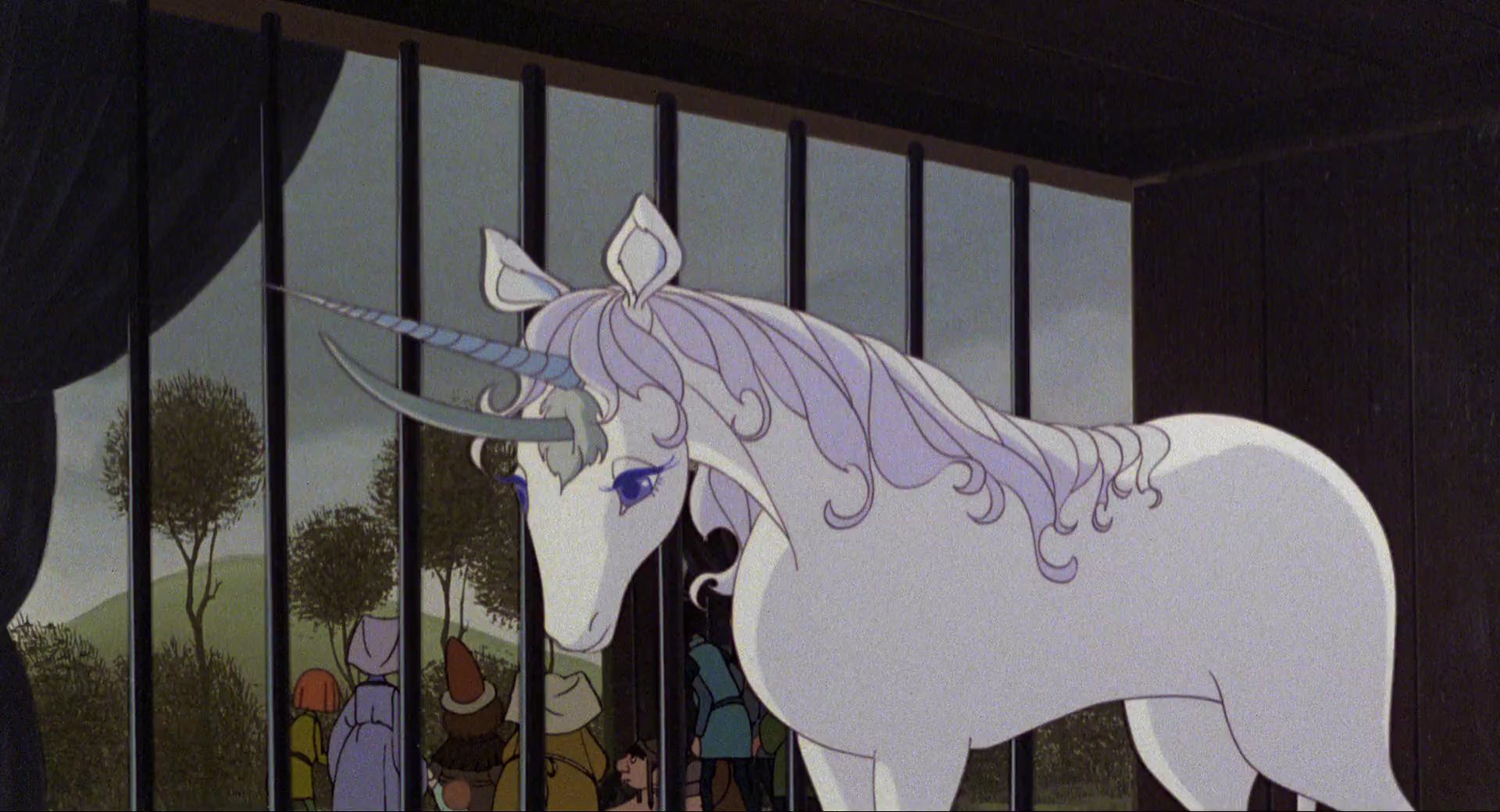

An archetype from the 1982 movie The Last Unicorn: The witch Mommy Fortuna (played by Angela Lansbury) captures the Unicorn (Mia Farrow) for her Midnight Carnival. People no longer believe in unicorns so she puts a false horn on the real unicorn so people can see her.

We put false horns on real unicorns because the emotional resonance of a simple fact often isn’t enough to inspire a desired change.

This is the game in politics/behavior change marketing: Whether our intentions are noble or nefarious, what false horn can we put on this unicorn?

Nature also puts false horns on real unicorns. When you avoid something smelly, you aren’t avoiding germs. The part of you that recoils from gross, smelly things doesn’t know what germs are. Your nose has evolved to put a false horn on that real, potentially pathogenic, unicorn.

When you tell your child that if they want to be big and strong or gain magical powers they’ll need to eat their vegetables, you’re putting a false horn on a real unicorn.

A lot of our societal debates aren’t even about unicorns themselves. They’re about which false horn applied to the unicorn will be most effective in getting everyone else to see the unicorn (which they can already see and are busy fashioning their own false horns for).

We are always stuck working with incomplete information but we need to act regardless. It seems to be pointing somewhere, and so we use what we can assure ourselves we are making the right choices. We put a false horn on the real unicorns.

100 years from now, scientists will think all of the false horns we’ve been putting on our Big Question Unicorns were SO CUTE as they proceed to invent a few more of their own.

On some level, all of our stories are simply false horns put on real unicorns so that we will be inspired to believe and follow the underlying lessons of those unicorns. This is our special ability.

We are soft, meaty, imperfect bodies and minds. We need a horn to grab ahold of.